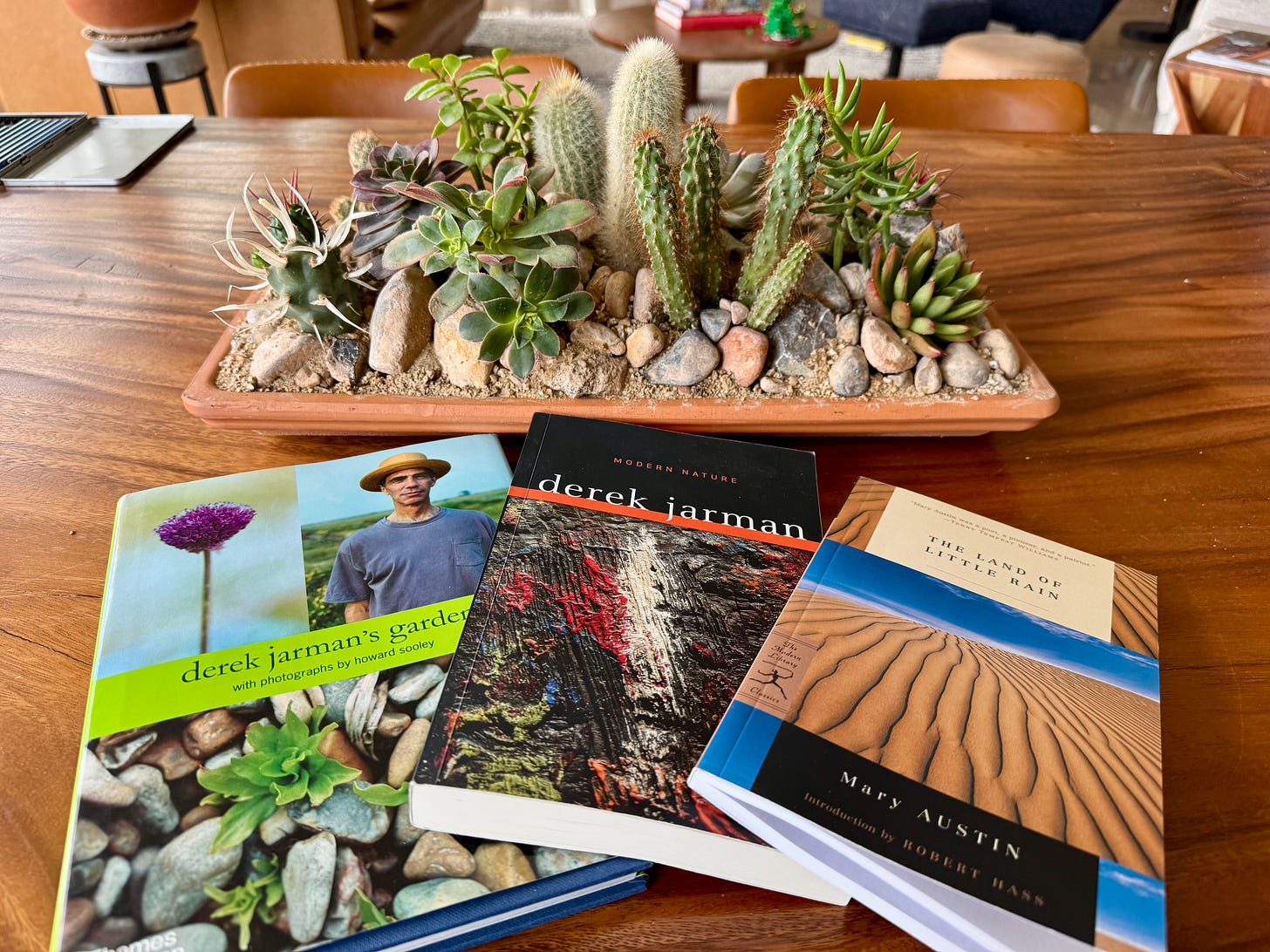

Book Review & Manifesto II: Derek Jarman’s Garden, Modern Nature, and Land of Little Rain

Another practical manifesto: “Build whatever you want but don’t demolish anything.”

It may at first seem strange to go to England seeking garden inspiration for the desert. Gardeners there get around 30 inches of rain a year, compared to the paltry four inches we get in the Mojave. In England, it doesn’t arrive evenly, and like many places around the world, drought comes more often and lasts longer. But the reason to study the island across the pond for desert gardening advice is a little cottage garden made by the late director, artist, and gay rights activist Derek Jarman.

Prospect Cottage is in Dungeness—a place I’ve never been, but since reading Jarman’s account of his gardening adventures there, both in the book, Derek Jarman’s Garden, and in his diaries published as Modern Nature—I’ve tasted salt and felt sun and stood wondering at the great billows of steam gushing from the nuclear reactor that overlooks his property.

If a garden can be built there, it can be built anywhere.

Good writing will do that for you. You can hardly leave your house and still visit the entire world.

There is a little Mojave in Jarman’s garden: bright orange California poppy. And there is a little Prospect cottage in my own, at the other end of the color spectrum: pale blue flowering rosemary.

This versatility is among the most extraordinary things about gardens and the plants that make them. Something that grows naturally under dry and windy skies with hardly any rain at all in the deserts of California and Nevada, takes root in equally inhospitable conditions in another part of the world. This fact forces us to rethink what we mean by hospitable, to change the received definitions of beauty. “Void of life, it never is,” said Mary Austin, speaking of the Mojave, “however dry the air and villainous the soil.” And later, in The Land of Little Rain, “for all the toll the desert takes of a man it gives compensations.”

Said Jarman of his garden one July, “The rain has brought the garden to life.” And Austin of the desert in spring after the scant rains of winter: “blossoming, radiant, and seductive.”

Villainous soil and ample compensations are certainly shared by Dungeness and the Mojave. The former is one of the largest shingle beaches in the world. A shingle beach is a gravel beach. While it receives rain, the earth is so porous that it retains hardly any water at all. Since it is close to the ocean, the vegetation that grows there (which is ample and much of it endemic, just like the Mojave) is buffeted constantly by salt and wind and sun, creating dwarfed and natural bonsai plant forms.

If there were ever an international garden program to match that strange sister city program, whereby cities in one part of the world are matched with cities in another part, like Las Vegas and Ansan, South Korea, I would pair the Mojave with Dungeness.

In Modern Nature, Jarman’s memory of his father coming to Nevada to watch an atom bomb demonstration returns here and there as a specter. The parallels are there like a subtle, sedimented haunting: a bad storm one year struck the nuclear power plant, bringing the area inches from nuclear meltdown, just as the a-bombs going off in the Nevada desert brought terrifying destruction to plant and animal and people. A father watches a mushroom cloud rising above the Mojave; years later, his son watches steam rise from reactors. Heat rises. Life rises. It all rises. In the desert, heat and thirst rise to produce a mirage as it does on the sea—mirages are everywhere. As are salt and sand and sun.

The first time I saw photos of Jarman’s garden I thought I was looking at an abandoned shack. There were few plants, and those there were, were clumped here and there. It seemed to me to be littered with garbage: scraps of rusty metal and worn sticks placed up right in the gravel with bits of metal hanging from them, old and disused garden tools and tire irons and wrenches. Trash really.

And then I looked and looked at the imagery and could not stop looking and suddenly all those found objects became sculpture. And the primary-colored drifts of red, yellow, and blue, valerian, gray santolina, and borage, became the dabs of a painter’s brush.

I saw that there was beauty, like Flaubert’s aesthetics of the ugly: a truly modern garden that could exist only there, in that place, by that person.

The Mojave offers these opportunities as well.

There’s a trend to turn our outdoor places into spaces: boring and interchangeable Euclidean planes that can be picked up and placed here or there.

But the beauty of the desert is in its rugged, utilitarian, aged and terrifying awesomeness. It is in its sparseness. It is in the skeleton weed as colder nights have come and the flowers have turned pink and the stems red so that the ground below my feet is an intricate web of brittle bronze and broken beauty.

I’ve said, despite my love of theory, that my writing here would offer practical advice for gardeners in arid climates. So, here is the practical part:

when choosing a mulch, find as much basalt and pink sandstone and conglomerate and broken mesquite and resinous creosote litter and the ribbons of shredded fan palms as you can and say no to crushed gravel and smooth river rock and dyed bark

let brittlebush get rank and weedy and overgrown (you can always cut it back)

collect interesting rocks like you would rare gems and place them where you can most admire them

forget to water fully two-thirds of your garden and when you do remember to water, be sporadic about it, with deep soaks here and just a light sprinkling there

allow the errant seedlings of Australian acacias and feathery cassias and weedy palms to grow where they are, so that wind and sun can shape them into daring sculptures

let your Texas rangers be rangy

shear your oleanders to the ground and withhold water until they are stunted and covered with clear, white blossoms that smell of musk and vanilla

let your desert garden look like here and nothing at all like Southern California or Phoenix, and if you are in California or Phoenix, let your garden look like Baja or Sonora while taking in whatever plants you can from all over the world

Then, you will have a garden with a point of view, an arid and beautiful wasteland to come back to again and again, so that you may with Jarman “dig in another time, without past or future, beginning or end. A time that does not cleave the day with rush hours, lunch breaks, the last bus home. As you walk in the garden you pass into this time—the moment of entering can never be remembered. Around you the landscape lies transfigured,” so that, in Austin’s words, “once inhabiting there you always mean to go away without quite realizing that you have not done it.”

Gosh I really really love your writing. Perhaps we could twin your desert garden with my weird gravel garden?! I’ve also long dreamed of visiting that amazing garden. I will now be looking into those books.